A terrifying new documentary carries a stark warning that a nightmare has been lurking in the medical industry for decades and it might be in your body.

The Bleeding Edge, which premieres on Netflix, examines the $400bn medical device industry responsible for products such as hip implants and robotic surgeons, through the lens of five products that have wreaked havoc on the lives of thousands.

“A wide range of people know about the problems with pharmaceuticals, but very few people know about the medical device industry and the fact that it is even less regulated than pharmaceuticals,” director Kirby Dick told the Guardian. “We felt it was very important that the public, doctors and policymakers know about this because right now medical device companies can get away with just about anything.”

Dozens of people speak about issues that followed procedures involving medical devices, including women whose intestines fell out of their bodies after robotic surgery. Doctors, too, come forward afflicted by the unknown effects of some of these devices.

Stephen Tower, an orthopedic doctor profiled in the film, had developed a tremor and was having a hard time thinking when he decided to scrawl all over the walls and ceiling of a hotel room during a medical conference, eventually using soap as ink.

Tower, his friends and family knew he was in the throes of mental health crisis, but no one was sure why. So, Tower studied himself until he found the answer in a blood and urine sample: his levels of cobalt, a metal used in rechargeable batteries, were more than a hundred times higher than normal.

Tower thought it might be related to his metal-on-metal hip replacement and had it redone. On the operating table, his surgeon found metal sludge seeping from the device before it was removed. “Within a month I had an incredible recovery in terms of my psychologic symptoms and ability to think,” Tower said.

Tower said he would never have believed neurological problems could come from orthopedic devices, if it wasn’t for that experience, and now tests the cobalt levels of his patients if they complain of having Parkinson’s or dementia-like symptoms.

Hundreds of thousands of people in the world may have been exposed to toxic metals from “metal on metal” hip implants, according to a 2012 joint investigation by the British Medical Journal and BBC Newsnight.

“If we can’t change the laws and we can’t convince companies to put moral issues above profits, then all of us really have to be vigilant,” said The Bleeding Edge’s producer, Amy Ziering. “My great hope is you watch this film and then you are really, really, really careful and ask a lot of questions and do a lot of research.”

A number of factors are responsible for the catastrophes captured in the film, but the documentary lasers in on the FDA’s 510(k) pathway for approving medical devices.

To approve a prescription drug, medicine must be tested in humans, the manufacturer must compile data on its effects and a panel of FDA scientists must give it final approval.

The same process is not required for medical devices. Those can be approved if the manufacturer demonstrates that it is equivalent to a device on the market – even if the device it is being compared to has been recalled.

“Even if we take these five devices that we focus on the film off, the problem isn’t solved,” warned Ziering. “It’s a system that needs to be much more vigilantly regulated.”

Despite the frightening situations depicted in The Bleeding Edge, portraits of hope come from people fighting back.

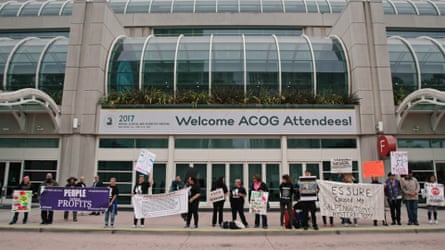

A week before the film was released, Bayer announced it would stop selling one of the devices targeted in the film: Essure, a coiled birth control implant that is inserted into the fallopian tubes through the uterus.

Women in the film who had the implant complain of persistent pain, bleeding and unintended pregnancies. They include Gaby Avina, a former spokeswoman for the device who had taken part in the original clinical trial for Essure. She said her health deteriorated after being implanted with the device.

On Friday afternoon last week, Bayer announced it would stop selling Essure at the end of 2018.

Bayer emphasized it decided to stop selling Essure for “business reasons”. The company said several factors had made it less popular among US women, including “inaccurate and misleading publicity about the device”.

As The Bleeding Edge depicts, that bad publicity has been driven largely by tens of thousands of women gathered in the Essure Problems Facebook group.

These women stage protests at medical conferences and Bayer’s headquarters (including one earlier this month) and hold in-person support groups for women who believe they have been harmed by the device.

Ziering and Dick said they were elated to see the product would no longer be sold less than one week before The Bleeding Edge’s release. “It’s really a tribute to all the women and all the work they’ve done,” Dick said. “It’s also a tribute to the power of documentary.”

But this success is not enough for either film-maker and they hope the public, lawmakers and medical community will push for change in the industry.

Dick said: “Millions of people have been harmed by medical devices and millions more will if nothing is done.”

- The Bleeding Edge will be available on Netflix on 27 July