Sweepers get the brush-off

Dennis Barker, 26 June 1986

The road sweepers lost out to the thespians in the 17-year battle over the Thameside Globe site yesterday. They will have to move out from the Southwark site – the scene of a prolonged legal dispute – so that the American actor and producer Sam Wanamaker can go ahead with his plan to construct a reproduction of Shakespeare’s Globe near its original site, part of which is now being used as a road sweepers’ depot by Southwark borough council.

Hard-headed romantic

Michael Billington, 20 December 1993

Sam Wanamaker, who has died aged 74, was best known in recent years for his doggedly heroic effort to establish a replica of Shakespeare’s Globe on its original Southwark site. Although the Globe will be his lasting testament, he was also a powerful Stanislavskian actor and versatile director whose career embraced everything from Tippett operas to Hawaii Five-O.

He had long been appalled by the fact that, while America boasted a number of Globe theatre replicas, the site of the Elizabethan original in Southwark was marked by nothing more than a plaque on a brewery bottling plant. So in 1970 he became executive director of the Globe Playhouse Trust and World Centre for Shakespeare Studies: the intention was not just to build a theatre but to create a museum and a centre of scholarship. In 1972, summer seasons were staged in a temporary tent. However, a freak thunderstorm capsized the production. “Although,” Vanessa Redgrave wrote, “Sam bailed out the water as fast as he could with a bucket, the show collapsed with the tarpaulins.” He was a hard-headed romantic driven by a passion for Shakespeare.

Theatre wars

Michael Billington, 13 September 1995

The thatched-roofed, triple-galleried auditorium is complete. The stage is still a temporary plywood structure. But around this stage a fierce debate has arisen between authenticity-seeking academics and pragmatic theatrical practitioners. Four weeks of public workshops ended with Peter Hall directing two scenes from his Stratford Julius Caesar in the new space. While paying tribute to “the existing beauty of the auditorium”, he was candidly damning about the two prominent downstage pillars that support the canopy over the stage known as the heavens. “The Elizabethan stage,” said Hall, “had both a major and a minor acting area at the side of the pillars. These pillars need to be much closer together and much further upstage. This mock-up is frightfully wrong.”

Andrew Gurr, who chaired many of the committees advising on the building, is unmoved. “Peter Hall is challenging the consensus of 120 international Shakespeare scholars who looked at all the available evidence and took the final decision that the pillars should be set far apart. It is also a matter of practical engineering. If Peter Hall wants the heavens to fall in on him, so be it.”

Verona to raise curtain

Michael Ellison, 28 March 1996

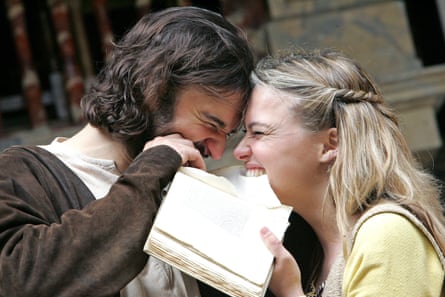

Mark Rylance has announced the first play to be performed in the £30m open-air building. The theatre, 300 yards from the site of the 17th-century original, will not be finished in time for its planned June opening. Instead, a prologue season of the Two Gentlemen of Verona will run from late August, with the first full summer season next year. “I’d like to see live radio broadcasts from here with someone like the cricket commentators explaining what’s going on, but I’m not so keen on television,” said Rylance. “I’ve never been able to sit through a Shakespeare play on television. I think that if you are going to film it, it should be a movie.”

Triumph of the Will

Michael Billington, 26 August 1996

“Authenticity” has always struck me as a pointless virtue in a medium that reinvents itself from age to age. But The Two Gentlemen of Verona works astonishingly well even on a chill summer night. The performance I saw began at 7pm and took place under highly un-Shakespearean artificial light. Authenticity – whatever that is – has been shrewdly tempered by theatrical reality. The overwhelming impression is of inn-yard intimacy. From where I sat, in the front row of the middle gallery, I saw and heard everything, though less fortunate spectators in the top gallery’s side seats obviously had an impaired view. The enclosed space, however, puts a new responsibility on audiences as well as players: I was awed by the resilience of the groundlings who stood for nearly three hours, but you quickly become aware of any distracting movement, such as the lady in tennis shoes and pac-a-mac looking for the loo.

Flattened by daylight

Michael Billington, 7 June 1997

It was all very English and low key. Shakespeare’s Globe opened – to the press anyway – not with trumpets and drums but to a half-full afternoon house watching a decentish production of The Winter’s Tale directed by David Freeman. What was lacking was any sense of occasion. It is too early to come to lofty conclusions about the Globe but it is evident that the building works best at night. Shakespeare’s actors played in the afternoon out of necessity, but daylight has a flattening effect on drama.

Blow the buggers’ minds

Mark Rylance’s boldest decision yet is to cast himself as Shakespeare’s temptress of the Nile. He says the actor Keith Baxter, a founder member of the Globe’s directorate, came up with the idea. “It was Keith, to my great surprise, who first suggested me for artistic director. When I got the job, to my even greater surprise, he promptly suggested that I actually open the place by playing Cleopatra. ‘Get on out there,’ he said, ‘and blow the buggers’ minds.’

“Well, even I thought that opening the Globe as Cleopatra might be a bit over-the-top. But the idea stuck in my mind. We’ve got way past the initial worries about casting young men in women’s roles – long since accepted by our audience far more readily than we dared hope. It’s wonderful how easily people make the leap of the imagination this place demands in so many ways.”

A busy aesthetic

Rylance is aware that productions at the Globe have not always dispelled the notion of the theatre as a Disneyesque tourist trap or a scholar’s plaything. He maintains that while actors are keen to explore the possibilities of the space, directors are more wary of a theatre whose intimate but roofless auditorium creates an unfamiliar relationship with the audience. He would love to get really good Shakespearean directors such as Declan Donnellan and Deborah Warner to stage productions. If they don’t come, it is not for want of being asked.

He concedes that both Donnellan and Warner in particular “have a puritan aesthetic, and the Globe is a busy aesthetic” but believes that other highly regarded directors may simply be reluctant to surrender control over the audience: at the Globe the closeness of the crowd to the stage means that the audience are never just passive spectators. Rylance looks rather hurt: “I do think it’s funny that so many of the people who supported the building of the Globe now don’t seem to want to work here.” If anyone could persuade the doubters to give it a go, surely it would be this gentle man held in huge affection by actors.

Drunkards, liars, adulterers

Many of Shakespeare’s plays can withstand the Globe’s pantomime atmosphere, but King Lear isn’t one of them. There’s something distinctly unpleasant about spotting two tipsy people flirting across the aisle while Gloucester stumbles about with his eyes gouged out. Barry Kyle’s gimmicky production encourages the restlessness, taking every opportunity to wink at the audience and thrust the actors among the groundlings. Edmund points at the balconies when he talks of “drunkards, liars, adulterers”; Kent storms through the audience into banishment; Lear’s rowdy entourage even involves the crowd in a game of catch.

Dark deeds and tinsel

“Come thick night,” intones Lady Macbeth as the sun blazes. It is a pretty tall order to pull off this play of dark deeds and darker psychology on a summer’s afternoon in broad daylight. It is not the sun, however, but his own wilfulness that scuppers Tim Carroll’s production. He begins as he means to go on with the trio of weird sisters (two men and a woman) dressed in dinner jackets and doing a jazzy dance. It could and should be smoky and spellbinding but, like so much in this production, it is just camp. Jasper Britton’s hapless Macbeth fingers gold tinsel instead of Duncan’s blood and you begin to wonder whether Birnam Wood will manifest itself as an army of fully decked Christmas trees.

Adventures in storytelling

Michael Billington, 12 July 2001

What to do with this Bankside playhouse? Mike Alfreds provides one of the best solutions I’ve seen, turning his back on the dreary concept of authenticity and offering us a production in the early style of theatre company Shared Experience. Six actors and two musicians in identical silky white costumes treat Shakespeare’s experimental late play Cymbeline as an adventure in storytelling.

Something old, something new

Peter Oswald is the first writer to pen new scripts for the Globe since (give or take a 17th-century scribe or two) the Bard himself. To Oswald, it is “naturally a space for new work”. Doubters are referred to his second play for the Globe, The Golden Ass, which takes satiric aim at godlessness and narcissism. It has for its creators as contemporary a clout as anything at the Royal Court. But the question remains as to whether new plays – or even, one day, plays with contemporary settings – will be accepted by audiences or critics as integral to the Globe’s activities. “We can’t win in one sense,” says director Tim Carroll. “Some people will always criticise it for being a heritage theatre, and others – sometimes the same people – will say, ‘What are they doing staging new plays?’”

Unsex me here

For seven years the company at the Globe has been experimenting with the unique relationship between actors, audiences and the architecture of Shakespeare’s theatre. We have explored modern theatre practices, sometimes radical modern practices, and what we call “original” theatre practices. I never call this work authentic. It isn’t. We choose the known practices that may be helpful to the modern relationship between actor and audience. Hand-made clothing, live music and dance of the period, not to mention single-gender casting, have created worlds close to the worlds of the building and the original writing. These practices may not be too familiar to modern audiences, yet our audience’s enthusiasm for such productions has inspired us to develop our understanding and skills.

Last year these experiments culminated in our all-male Twelfth Night. This year the Globe is going further and presenting four productions with single-gender casts. Two – Richard II and Marlowe’s Edward II – will be all-male. And, for the first time, two will be all-female. Of course, an all-female cast was not possible in an amphitheatre in Shakespeare’s day, when only male actors were employed. Shakespeare and his fellow actors, however, were not limited by the gender of the parts they played. They enjoyed a theatre of the imagination, where commoner played king, man played woman, and, within the plays, woman man. In Shakespeare, the disguise and revelation of everything, including gender, is central.

Away from whimsy

Michael Billington, 12 May 2006

It’s early days, but I detect a new spirit at the Globe. For a start there is an intellectual coherence about Dominic Dromgoole’s opening season, with its stress on Shakespeare’s Roman plays. Even more significantly, this Coriolanus is a strongly cast, ensemble affair rather than the kind of star-driven, Wolfitesque spectacle often seen at this address. His approach to the play is clear, sensible and practical. He stages it in Jacobean costume, reminding us that Shakespeare’s confrontation of a patrician class with a hungry, rioting mob has an urgent topicality.

In praise of ... the Globe

Guardian leader article, 1 June 2006

Almost a decade after it opened, the Globe remains an eye-popping sight, all wood, white plaster and thatch. But early fears that its performances would lapse into doublet-and-hose, animating merrie England for transatlantic tourists, have given way to respect for the Globe as a cultural venue. Mark Rylance set the pace with a series of vigorous productions, including Shakespeare’s lesser known plays, and proved that the theatre could attract an audience. It makes a profit of around £1.5m a year, despite low prices, especially for open-air standing places, and an absence of government subsidy. This year, under the banner “the Edges of Rome” Dominic Dromgoole is putting on four Shakespeare plays and two new works, by Howard Brenton and Simon Bent. The theatre will never be able to equal the RSC’s complex modern productions in Stratford, which this year include all 37 Shakespeare plays. But that is not why it was built. The Globe’s reconstruction was a miracle of persistence. Against the odds, its productions more than live up to their wonderful setting.

The whole place is aroar

At the Globe there are two distinct ways to experience Titus Andronicus. Seen from the more expensive seats, Lucy Bailey’s production is impressive; seen from the yard, where you can stand as a groundling for a fiver, it’s explosive. Down there, processions carry leaders aloft through the crowds; huge iron trolleys rattle past bearing triumphant warriors; black paper floats down like cinders; spectators are co-opted as citizens, orated at and teased. The action of the play starts unpredictably, behind you as well as in front; the yard turns from auditorium to thoroughfare; the whole place is aroar.

Ghosts and groundlings

Having my play In Extremis performed at the Globe was terrifying: this was something like the space for which Shakespeare wrote. The building may be a modern reconstruction, but its stage, its “groundlings” yard, its high, secret galleries, are full of ghosts. Would my play wither by comparison, to hoots of spectral derision from the shades of the first penny-paying “groundlings”? I need not have feared. By the end of the first run of In Extremis last year – it is revived this week – I felt this is what the theatre should be. At the Globe, the audience is much more powerful than in a conventional theatre. You can see each other. People walk about and come and go, without affecting the performance. They are also much more vocal: laughs are quicker, responses seem sharper. Eye contact between performers and spectators builds a sense of shared undertaking. Asides are powerful: that is why so many of Shakespeare’s psychological insights are dramatised straight to the audience in soliloquies. Conventional theatres – by the dimming of house lights – try to obliterate themselves during a performance. At the Globe, the presence of the building dominates.

Fools and families

Dromgoole’s King Lear gets down to the storytelling with minimal fuss, and understands that there are many kinds of fool and many kinds of families. Lear and his loyal friends out on the heath join hands against the pitiless stars and for a moment I was irresistibly reminded of another raggle-taggle, self-constructed family up against the world: Dorothy and co from The Wizard of Oz. There are also some genuine five-star moments: Lear and Edgar hugging each other in recognition of a shared pain; Lear’s sudden flash of understanding of his own vulnerability in the cry, “I would not be mad” – a line that makes your heart go into freefall.

At the Frontline

Michael Billington, 11 July 2008

The best feature of the Globe, under Dromgoole’s management, is the balance between classic and contemporary work. Che Walker acted here in Othello, but the key influence on his robustly enjoyable new play, The Frontline, is not Shakespeare but Ben Jonson. Imagine Bartholomew Fair translated to the precincts of Camden Town tube station on a Saturday night and you get some idea of his work’s topographical vigour.

Swagger and sack

Henry IV is the Shakespeare play that’s perfectly suited to the Globe. In Dromgoole’s intelligent, faithful and entertaining new production, Sir John Falstaff, that “sweet creature of bombast”, might have stopped for a pint of sack in Southwark en route to a rendezvous with Doll Tearsheet at the Boar’s Head. Starring Roger Allam as the swaggering, clownish mentor to Jamie Parker’s Prince Hal (the “tutor and feeder of my riots”), the Globe’s players deliver a delightful reading of Shakespeare’s hit play of 1597, making it seem what audiences most desire: evergreen and universal.

Artists not politicians

The final image of this Merchant of Venice by the Israeli company Habima is a stark one. Small and crushed, as if weighed down by history itself, Jacob Cohen’s broken Shylock – a man who has lost daughter, fortune and home – is seen, suitcase in hand, walking away from Venice, an eternal wandering Jew. But it was impossible not to think of other displaced people, too, most particularly the Palestinians.

This was inevitable, perhaps, during an evening that held as much drama off stage as it did on: pro-Palestinian protests were held both outside the theatre and during the performance. For much of the first half, a woman stood up in one of the galleries in silent protest, her mouth taped shut. Others were removed. Dominic Dromgoole asked for the audience to respect the performers. “You’re not watching politicians or policy-makers,” he said. “You are watching artists who are here to tell a story.”

Uncontrollable desire

Michael Billington, 18 November, 2012

For those of us who favour good sightlines and acoustics, the transfer of Twelfth Night and Richard III from the Globe to the West End is welcome news. Both feature an all-male cast, and are directed by Tim Carroll and designed by Jenny Tiramani. The big draw is Stephen Fry’s Malvolio, and he acquits himself extremely well. He is suitably grave, dignified and overbearing. My only reservation is that Fry has such natural lordliness and is so handsomely bearded that you feel he would be a catch for any Olivia. Class revenge, which motivates the plot against the presumptuous steward, is less a factor in this version than is the idea of passion breaking through a stonewall surface. You see exactly that, to hilarious effect, in Rylance’s Olivia, a performance that shows the stylised movements and white face of the onnagata (female impersonator) from Japanese kabuki theatre being shattered by uncontrollable sexual desire.

Gaudy glory of The Tempest

Roger Allam is Prospero. He is so natural that he commands the stage without raising his voice. He never plays the magician, but neither is he dully conversational. It is as if he controls the action not by supernatural powers but by human qualities: by being more rational, more self-knowing than anyone else.

This is pure Globe. Gallimaufry, gaudiness, moments of glory. Where else do telly and Shakespearean stars jumble and jig together so easily? Where else do doublet and hose co-exist with such a dynamic, interventionist relation between actors and audience?

‘We’re not going to leave anyone out!’

The Globe is sending a production of Hamlet on the first genuine world tour in theatre history. Starting on 23 April 2014, the 450th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth, the company will spend two years travelling by planes, trains, boats and buses to visit every nation on Earth – 205 countries in all. “I think having a lunatic idea is a very good thing. It’s a great way to keep everybody focused and dazzled and delighted by the ambition and energy of the company,” said Dromgoole. “If we’re going to do every country in the world it has to be every country, we’re not going to leave anyone out. All the ’stans, South and North Korea – we’re very keen to get into North Korea. Antarctica? Fuck yes.”

An intimate partner

The reconstruction of the Globe, designed by the late Theo Crosby, could have been pure kitsch, a Madame Tussauds-grade piece of tourist tat. That it manages to be a serious and adventurous theatre is down to its artistic direction, but also to its fabric. There is the striking, daring fact of it being open-air in a soggy climate. There is also its literal-minded pursuit of thatched-roofed, green-oak authenticity with a conceptual rigour that would make it worthy to enter the collection of the nearby Tate Modern.

Now, a 340-seat Jacobean theatre has been created in the Globe complex, called the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse. Planned long ago, it occupies a brick shell – built to house it at the same time as the Globe itself was reconstructed – which has been temporarily inhabited by education spaces and other uses. The playhouse is designed by the architect Jon Greenfield, in collaboration with Allies and Morrison, and it raises the stakes again. It is a roofed-over space, intimate and intense, where the people in the best seats – to the sides of the stage – are in touching distance of the actors.

Flying octopuses

Michael Billington, 5 September 2014

I’ve always thought The Comedy of Errors to be one of the most beautifully crafted farces ever written. What is refreshing is to find it given a near-perfect production by Blanche McIntyre. Fastidious attention is paid to speech. In the passage where the Syracusan Dromio describes being pursued by a gargantuan kitchen wench, Brodie Ross makes every word count so that when he says, “She is spherical – like a globe,” the audience roars with delight, picking up the obvious allusion. There is plenty of physical fun with masters and servants hurling everything possible, including a dried octopus, at each other and with James Cotterill’s set at one point threatening to disintegrate like the temple in Cecil B DeMille’s Samson and Delilah.

‘I’d love it if they booed me’

At the age of 67, Jonathan Pryce is making his debut at Shakespeare’s Globe, playing a much-anticipated Shylock. The role, he admits, is getting to him. “I don’t worry normally, but with this one …” He brushes an imaginary piece of lint off his trouser leg. “I haven’t worried about anything so much for years. I hate that phrase ‘comfort zone’, but Shylock is definitely way out of mine.” Previous Shylocks at the Globe have borne the brunt of the audience’s displeasure: at least one was booed. Is he worried the same might happen to him? The smile reappears, this time entirely wolfish. “Oh, I’d love it if they booed me. I’d find that fascinating.”

Just another groundling?

Catherine Love, 28 September 2015

The first time we see Gugu Mbatha-Raw as Nell Gwynn, she’s one of us. In this rowdy retelling of Nell’s rags-to-riches life, the famous restoration actress starts among the groundlings as just another admiring – if mouthy – spectator. Soon, though, she’s treading the boards herself, first at Drury Lane and then on the nation’s stage, as the favoured mistress of King Charles II. Both Jessica Swale’s text and Christopher Luscombe’s production are playfully conscious of their theatrical surroundings. Nell Gwynn is a play about theatre as much as anything else: its joy, its artifice and its uneasy marriage of entertainment and education.

‘Desperate for a good night out’

“Inside I’m rocking like a kid on a school trip who can’t wait to get there. I can’t wait to get an audience in front of me,” says Emma Rice, who is directing A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the first play in her debut season as the Globe’s new artistic director. She has been working on a manifesto for the theatre’s actors and directors; it begins with the line mangled by Quince, one of the amateur actors, in Dream: “Our true intent is all for your delight.”

Rice reckons that’s a good maxim for her tenure because “the audience is at the heart of everything the Globe does”. It has to be, because the theatre has no subsidy: if it doesn’t sell tickets, nobody gets paid. “That dialogue between the stage and the audience is what attracted me to the job. It’s like a love affair. There’s still some snobbery about it, and talk about the Globe being only for the tourists. I don’t see a tourist audience. I see a young, fit, adventurous audience who are desperate for a good night out.”

Thumping good fun

Shakespeare’s comedy of Petruchio’s plot to woo the unmarriageable Katherine is unpopular in theatre – the heroine’s submission to her husband’s tyranny now considered literally unspeakable. Paradoxically, however, The Taming of the Shrew is a source for populist modernisations in other forms such as Cole Porter’s musical Kiss Me, Kate. This contradiction is solved in Caroline Byrne’s splendid revival, which stages The Taming of the Shrew as thumping good fun while also taming the play’s ideological toxicity. The production is set in 1916, the time of a defining fight for independence in Ireland. Although references to “Italian” have been changed to “Irish”, and the accents are those of Dublin and its surrounds, the settings of Padua and Verona are kept, giving the confusing impression that the characters are on a Ryanair city break.

Renamed and reclaimed

Michael Billington, 25 September 2016

Tennyson loved Cymbeline so much he had a copy of it buried in his grave. He might well be turning in that same grave if he could see this new version, “renamed and reclaimed” by Matthew Dunster. I rate Dunster, who did a great job on Martin McDonagh’s Hangmen, highly as a director but I fail to see the point of translating Shakespeare’s experimental romance to a grungy East End world of drug-dealing, garage music and sadistic torture.

Egg on its face

The news that Emma Rice will be leaving the Globe in 2018 after just two seasons – including a critically acclaimed first season that delivered exceptionally strong box-office returns – reveals an organisation that is deeply divided about its purpose, and now has egg on its face. Why appoint Rice, best known for her internationally renowned work with Kneehigh, if you are not going to back her? Had nobody seen any of her productions? Or maybe they didn’t properly listen to her plans for the theatre during the long and rigorous interview process.

“The Globe was reconstructed as a radical experiment to explore the conditions within which Shakespeare and his contemporaries work, and we believe this should continue to be the central tenet of our work,” said chief executive Neil Constable. The message is clear: the Globe is not really a theatre but part of the heritage industry and a plaything for academic researchers.

What does the Globe stand for?

Emma Rice has broken her silence over her departure, saying she left because of a lack of respect from the board, and exclusion “from the rooms where decisions are made”. Rice and her predecessor, Dominic Dromgoole, have written open letters that shed new light on one of the saddest chapters in the 20-year history of the theatre. In her letter, Rice writes: “Never think that my decision to step down in 2018 was simply about lights and sound, it was about personal trust and artistic freedom.” She believes the Globe is “wrestling with what, at its core, it now stands for”. “I had to choose to leave because I choose myself and my work,” she writes.

The application process for Rice’s replacement closes on 24 April with interviews in mid-May. The advertisement calls for “an experienced and dynamic theatre professional with a love and knowledge of Shakespeare”. Whoever it is will be “the latest in a line of experimental radicals and you will be in for the most intoxicating experience of your life,” Rice writes.