The renowned Lod Mosaic, excavated in 2009, is on exhibit at the Penn Museum through May 12, 2013. This is the Mosaic’s last stop in the United States, before it travels to Europe and then back to Israel.

Rina Talgam, specialist in ancient wall paintings and mosaics, describes the context and the significance of the mosaic.

The mosaic floor from Lod is one of the most spectacular mosaics ever discovered in Israel. It was unearthed in a salvage excavation conducted at the site in 1996 by Miriam Avissar on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The mosaic was then covered over until it could be conserved. Four years ago, it was unearthed again in order to remove it from the site. It will be returned to the place where it was discovered when a new visitors’ center is completed.

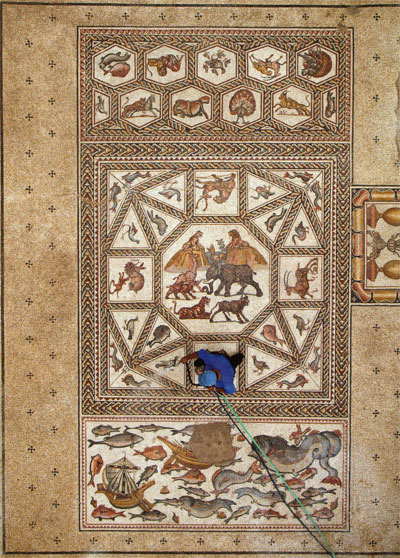

The almost perfectly preserved mosaic (measuring more than 17 by 9 meters, or approximately 56 by 30 feet) reveals the splendor of an ancient Roman city. Lod (Lydda) was located at the intersection of a number of important routes and was a leading textile production center in antiquity. From 70 CE until the 4th century it was an important Jewish city; in 199 CE it became a Roman colony and was given the name Diospolis. Coins with depictions of temples and pagan deities that were minted in the 3rd century indicate that the population at Lod included pagans as well as Jews. There was also a small Christian community, and during the early 4th century the city had a bishop.

The Lod Mosaic dates to the end of the 3rd or the beginning of the 4th century. It has no dedicatory inscription so it is hard to determine with assurance the religious and ethnic identity of its patron. The content and style reflect a Roman influence, but the lack of human figures hints at the Christian or Jewish identity of the owner. The mosaic floor probably decorated the reception hall of a villa, although the exact architectural context is unclear, since most of the walls of the structure were looted. Nevertheless, the floor’s quality and size indicate that the owner was a man of means.

The Lod Mosaic is significant for several reasons. In striking contrast to most of the mosaics of Palestine in the Late Roman period, it reflects strong ties with North Africa. The provincial elite of Palestine usually regarded Antioch (capital of the Province of Syria) as a model to emulate. Consequently the themes and compositions reflected in mosaic floors continued the Hellenistic artistic tradition. In the Lod Mosaic, however, the focus on Greek mythology gave way to other themes, such as animal games ( venationes ) that took place in the arena of an amphitheater. The basket full of fish that appears in the mosaic is a motif associated with Roman North Africa, while the two boats in the marine panel are of a type of merchant vessel common in the western Mediterranean.

The openness of the patron to alternative models originating in the Latin West is not limited to iconography but is also attested by the arrangement of the floor. A typical Hellenistic composition, characterized by the use of emblemata (images that create an impression of three dimensions), was replaced by a “non-classic” perspective, in which the uniformity of the floor as a flat surface was achieved by the use of a geometric grid inhabited with figures. Even the central hexagonal medallion with the Nilotic landscape does not reflect a traditional Hellenistic pictorial rendering, but gives the impression of a collage. This new repertoire and style expressed the Roman identity of the patron, but it also reflected the “social reputation” of the North African style at this time. At the end of the 3rd century and beginning of the 4th century, the new style had also reached other parts of the Roman world, including Italy. It is most impressively visible in Piazza Armerina in Sicily. The Lod Mosaic extends the reach of this artistic trend into Roman Palestine at an earlier stage than its first manifestation in Antioch.

The diffusion of artistic ideas from West to East took various forms, passing through numerous channels of transmission. In the case of the Lod Mosaic, the derivation was direct and reflects rather surprising inter-provincial relationships. Several stylistic features indicate that the mosaic was produced by local artists. The local element is especially reflected in the style of the animal figures throughout the floor. In the marine panel, the lack of marine deities emerging from the water and the inclusion of the boats attest to North African influence, but the water of the sea is not rendered in the conventional treatment of water in North African mosaics, where it is represented by broken zigzag lines filling the spaces between the figures. The solid background of the sea in the Lod Mosaic matches the artistic conventions of Antioch and Roman Palestine.

The Lod Mosaic is at the crossroads of the Hellenistic East and Latin West, as it includes Greek and Roman components as well as local elements. But the importance of the mosaic goes beyond that. It reflects the transition from classical to early Byzantine art and contains compositional and stylistic features that led to later artistic developments. The artists who made this magnificent floor did not sign their work, but their footsteps remained on the mortar that served as the foundation of the mosaic.

– Images Courtesy of Israel Antiquities Authority

For Further Reading

17 (1998): 169-172.

Ovadiah, A., and S. Mucznik. “Classical Heritage and Anti-Classical Trends in the Mosaic Pavement of Lydda (Lod).”

Assaph. Studies in Art History 3 (1998): 1-18.

Schwartz, J. J. Lod (Lydda), Israel: From its Origins through the Byzantine Period, 5600 B.C.E.–640 C.E. , BAR International Series 571. Oxford: Tempus Reparatum, 1991.