Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

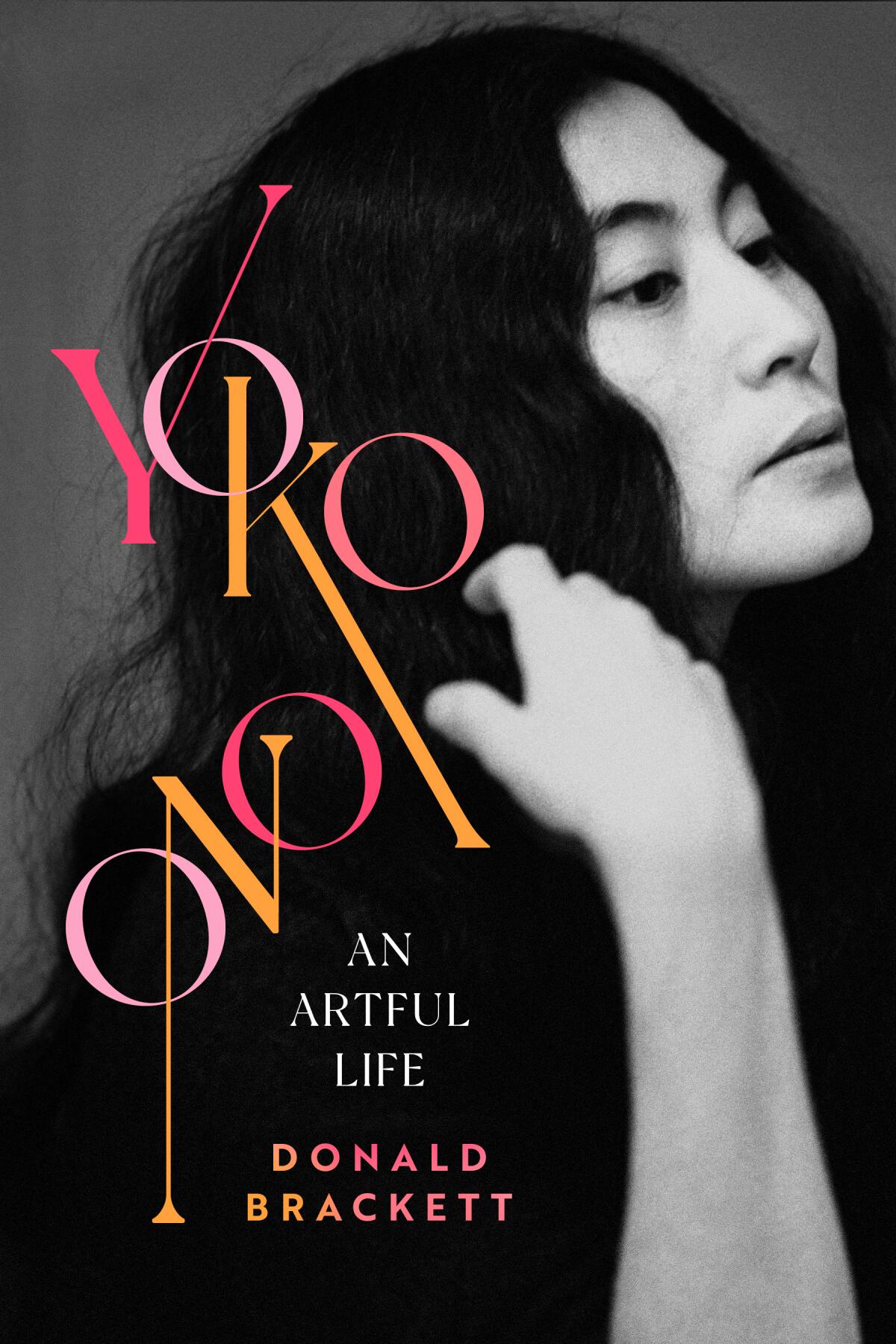

On the Shelf

'Yoko Ono: An Artful Life'

By Donald Brackett

Sutherland House: 350 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

On April 3, 1961, Yoko Ono’s piece “Of a Grapefruit in the World of Park” was performed at the Village Gate in New York City. The New York Times covered the show; in the photograph that ran in the paper, Ono was cut from the frame.

Ono is known to most as the woman responsible for breaking up the Beatles. “She has been reviled as a drug addict, bad parent, and careless wife, and dismissed as a shock artist and talentless attention-seeker with puerile ideas and bad taste,” Donald Brackett writes in the introduction to “Yoko Ono: An Artful Life.” “Perhaps no other artist in our times has been subject to as much racism and misogyny.”

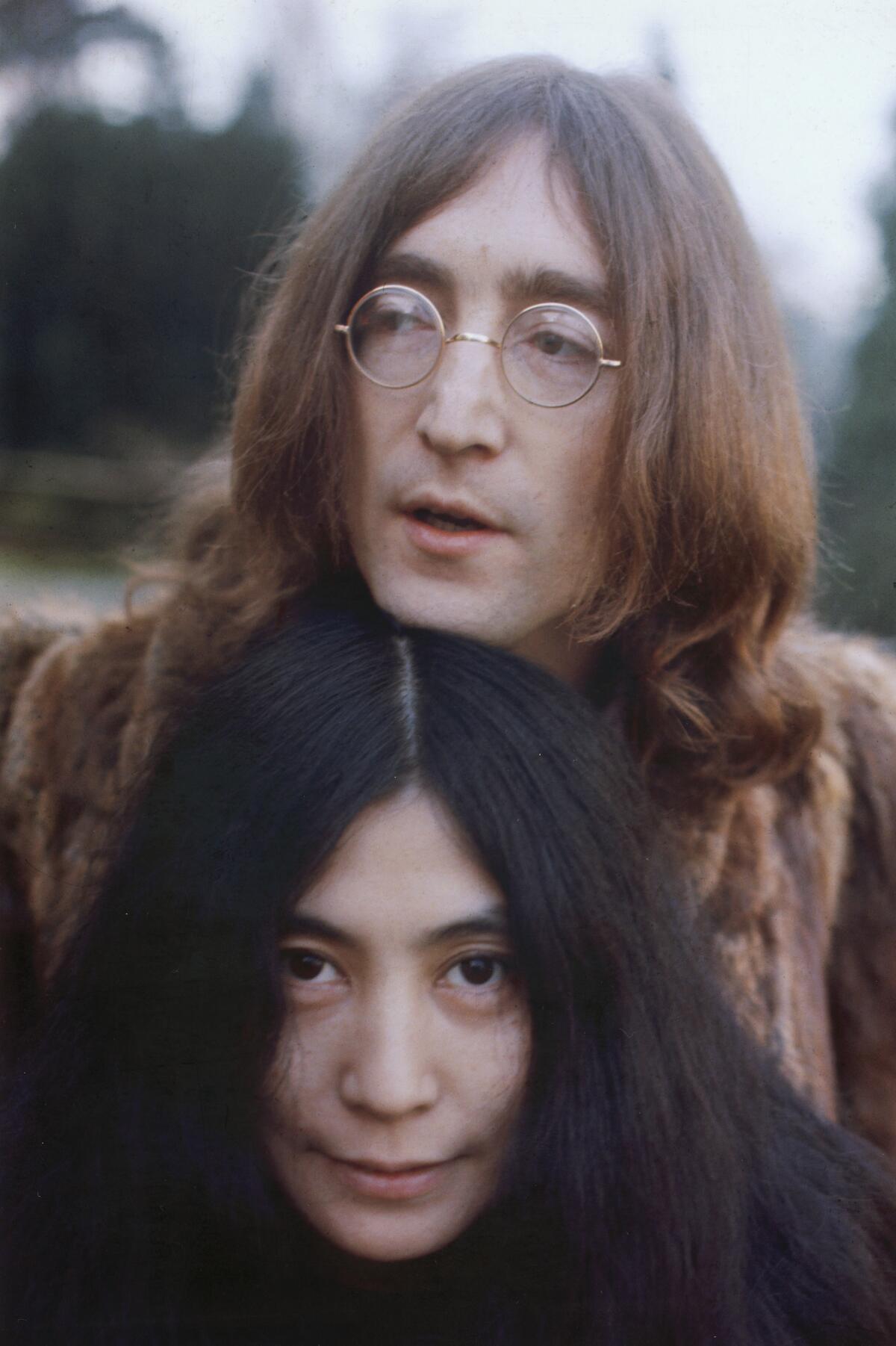

Brackett is a critic and the author of books on Tina Turner, Amy Winehouse and Fleetwood Mac. His new biography comes on the heels of Peter Jackson’s Beatles documentary “Get Back,” released on Disney+ over the winter holidays. In the nearly eight-hour-long chronicle of the recording sessions that spawned “Let It Be,” Yoko arrives with John Lennon, installs herself near him and never leaves.

John and Yoko are inseparable in our consciousness as well. Brackett is well intentioned — “the point of this book is that [Ono] had a fascinating and important life of her own apart from [Lennon], one worthy of consideration on its own merits.”

And yet Lennon is murdered on Page 197 of this 237-page narrative, leaving 40 pages to cover as many years to follow. Much of the book reads like the Yoko chapter in a biography of John. The siren song of Lennon/McCartney once again drowns her out.

When she met Lennon, Ono was an established artist, one of the founding members of Fluxus, a community of experimental artists that included composer John Cage and video artist Nam June Paik. Her star was on the rise in New York and London.

Friday a little after 10 p.m., Walt Disney Concert Hall once more became the site of a history-making moment.

Performance art wasn’t quite a thing yet. Or rather, it was a thing without a name. Ono’s “Cut Piece,” first performed in 1964, involved Ono sitting on the stage and inviting audience members to cut pieces of her clothing off until she was left practically naked. It feels like a tamer version of Marina Abramović’s “Rhythm 0,” in which attendees were presented with 72 tools to use on Abramović, including razor blades, an ax and a loaded gun. “Cut Piece” preceded “Rhythm 0” by 10 years.

“It is quite likely that having John Lennon fall in love with her was the worst thing that could have happened to Yoko Ono’s art career,” critic Robert Palmer wrote in the liner notes for Onobox, a collection of her complete recordings. By the time she met the Beatle, she was internationally known. Then she became, as Philip Norman wrote, Lennon’s “fiercely unglamorous-looking Japanese” girlfriend “from the art world’s lunatic fringe.”

Brackett does an excellent job of calling out the racism and misogyny that continues to follow Ono wherever she goes. When Bob Dylan and Miles Davis wouldn’t tell their studio musicians what they were going to be playing in advance, they were doing it to “knock them out of their well-worn grooves.” When Ono did the same thing, it was labeled “unprofessional.”

In fact, Ono was intensely purposeful in her music. Trained as a classical singer, she could’ve gone on to an operatic career but wasn’t interested. “I was dying to scream,” she said. “I wanted to throw blood.” One of the most extraordinary tracks on her 1970 debut album, “Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band,” is “Greenfield Morning I Pushed an Empty Baby Carriage All Over the City,” about the first of many miscarriages during her relationship with Lennon. Listening to this song is like pulling the lid off a jar that contains centuries of women’s suffering.

Brackett discusses primal scream therapy and the art of kabuki as influences on the Plastic Ono Band and gives Ono long-overdue credit for collaborations with Lennon. In later interviews, Lennon admitted that Ono had written “Julia” and that “Imagine” “should be credited as a Lennon-Ono song. … But those days I was a bit more selfish, a bit more macho, and I sort of omitted to mention her contribution.”

“Society doesn’t understand that the woman can be castrated, too,” Ono said in a 1980 interview for “Playboy.” “I felt castrated. Before I was doing all right, thank you. My work might not have been selling much, I might have been poorer, but I had my pride. But the most humiliating thing is to be looked at as a parasite.”

Peter Jackson and ‘Let It Be’ director Michael Lindsay-Hogg explain how 57 hours of footage from 1969 tell a different story in ‘The Beatles: Get Back.’

Brackett’s discussion of Ono’s approach to motherhood honors her radical sensibilities. “She refused to apologize for leaving primary care of her child with her husband, an unusual step at the time,” he writes, giving Ono ample room to explain her own perspective: “The responsibility is shared.”

But here’s the rub: These revelations still define Ono in relation to Lennon. There remains a deep hole where Ono’s experimental films, performance art, instruction pieces and activism should be.

Describing her film “Fly,” which shows a fly walking over the body of a naked woman, Ono said the mystery of whether or not the body is living is intentional. “This whole idea of a male society was based on the fact that women shut up … but shutting up is death in a way. So we were always kind of pretending to be dead.” The parallels to rape culture and the #MeToo movement are palpable, though “Fly” was released in 1970.

Her work over the last 40 years — “Wish Tree,” “Earth Peace,” “Skyladder,” “Arising,” “Skylanding,” “Refugee Boat” — all spread the explicit message of peace, unity and communication. Her “Peace Tower” in Reykjavík, Iceland, is illuminated every year for Lennon’s birthday. On Feb. 24, Ono announced that the tower would be lighted “to show solidarity with Ukraine and emphasize the call for peace.” To call her the most committed antiwar artist of the 20th century is not an overstatement.

Of those famous “Let It Be” sessions, Paul McCartney said in 1969, “It’s going to be the most comical thing in 50 years, that the Beatles broke up because Yoko sat on an amp.” She wasn’t merely sitting — she was painting, singing, screaming and giggling at Beatles fan zines while the band disintegrated around her. And whatever you make of McCartney’s tossed-off prediction, the accusation isn’t comical at all.

The painter known to many as Lucian Freud’s one-time muse writes of her own muse, her mother, and provers herself a masterful writer as well.

At the Cannes Film Festival in 1971, Ono wrote an essay in answer to her own question, “What is the relationship between the artist and the world?” Her answer sheds light not only on her oeuvre but also, perhaps, on her time in that studio. “The job of an artist is not to destroy but to change the value of things. And by doing that, artists can change the world into a Utopia where there is total freedom for everybody.”

In the closing pages of his biography, almost as an aside, Brackett states there is no mention of Ono in Linda Nochlin’s seminal 1971 essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” He’s right to point out the oversight. Yoko Ono is a great artist. If only we could begin to see her as one.

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.