By ADBL editor Corey Brennan

A prized student of Canova. An admired collaborator of Thorvaldsen. Later, an internationally acclaimed sculptor whose client list included Prince Metternich, the future Alexander II of Russia, and Queen Victoria. He was commissioned to create monumental works that stand in Messina, Caracas, Bogotá and (at least for now) Sydney. In Rome, he served as president of the Accademia di San Luca, and then successively as head of the Capitoline Museums and director of the Vatican Museums. He even sculpted a Papal tomb in St Peter’s, that of Pius VIII Castiglioni (reigned 1829-30), executed in the years 1853-1866. In short, the prolific neoclassical sculptor Pietro Tenerani (Torano di Cararra 1789—Rome 1869) firmly won a place as Canova’s spiritual heir and one of the artistic giants of his generation.

Where can you see Pietro Tenerani’s work? Well, as it happens, at this precise moment (and until 12 November 2023) the Museo di Roma at Palazzo Braschi is hosting “Vis-à-vis. Tenerani Spina. Dialogo in Immagini“—a major exhibition of 25 plaster busts by Pietro Tenerani paired with portrait photographs by Luigi Spina (born 1966).

Which brings us to the point of this note. It now emerges that the Casino dell’Aurora has an important neoclassical bust signed by Pietro Tenerani. As a modern work, it did not find a place in Beatrice Palma‘s essential 1986 survey of the ancient marbles in the Casino dell’Aurora. A 2005 inventory did take notice of the piece, describing it as “a portrait head of a female figure with a bust of a young woman dressed ‘in the ancient style’ with elaborate hairstyle, white marble, not attributed, 19th century”. The expert 2019 court-ordered inventory of the Casino’s immobile ancient and modern art does not mention it. Indeed the sculpture can fairly be described as so far unidentified and unpublished.

I first saw this 19th century piece at the Casino dell’Aurora in 2010, thanks of course to HSH Prince Nicolò and HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi. It is not a sculpture that catches the eye—since it is displayed in a low niche on a staircase landing. I mentioned at the time that the sculpture looked like the school of Canova. Princess Rita’s working hypothesis was that it was a portrait of the Catholic British noblewoman Lady Gwendoline Talbot, later Princess Borghese (1817-1840)—the third great grandmother of Prince Nicolò. A few years later, my ADBL colleague Anthony Majanlahti said he thought it was by Pietro Tenerani. It was only in October 2019 that I managed to photograph the bust from all sides, and (gulp) July 2023 that I noticed from those photos Tenerani’s signature.

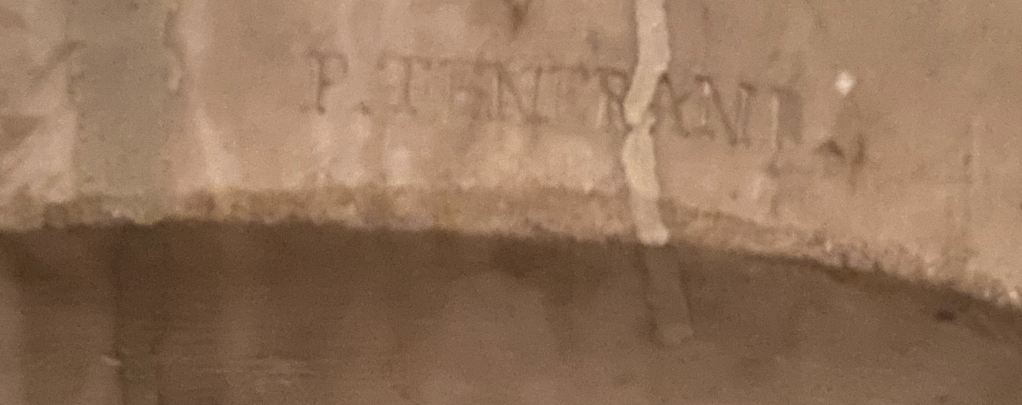

Detail of rear of 19th century bust in the Casino dell’Aurora, with signature P. TENERANI. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome. Photo: TC Brennan

Detail of rear of 19th century bust in the Casino dell’Aurora, with signature P. TENERANI. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome. Photo: TC Brennan

What about the subject? The fascinating story of the Talbot sisters Lady Mary (born 1815) and Lady Gwendoline (born 1817) can be told here only in outline. Their parents were John Talbot, the 16th Earl of Shrewsbury (1791-1852), and Maria Theresa Talbot (1795-1856); four siblings died in infancy. At a young age, the sisters showed remarkable proficiency in Italian, French and German; at age seventeen, Mary received the title of “Princess” from Ludwig I of Bavaria, and nearly was engaged to a German prince, Friedrich of Saxe-Altenburg. Yet it was the family’s frequent visits to the city of Rome that had the greatest impact on the young women, who in turn—as Anthony Majanlahti has emphasized to me—went on to change 19th century Rome.

Andrew Geddes (1783-1844), study for a painting of the Ladies Gwendoline and Mary Talbot. Credit: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art / Creative Commons.

Andrew Geddes (1783-1844), study for a painting of the Ladies Gwendoline and Mary Talbot. Credit: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art / Creative Commons.

In 1835, aged not quite 18, Gwendoline married Prince Marcantonio Borghese, becoming Princess of Sulmona. To the surprise of pretty much everyone, immediately after marrying she devoted her chief energies to helping the poor of Rome, with tireless visits to crowded hospitals and indigent homes. Then in 1839 Mary was married, to Prince Filippo Andrea V Doria Pamphilj Landi; the two probably had first met at the coronation of Queen Victoria in June 1838. On moving to Rome, Mary joined her sister Gwendoline in vigorous hands-on charity work.

Yet Gwendoline died suddenly on 27 October 1840, aged 22, in the midst of a cholera epidemic. She left four young children, a daughter Agnese (born 1836) and three sons (born 1837, 1838 and 1840). Within a few weeks, all three of the sons were also dead. The loss of this young princess and her sons sent Rome into a frenzy of grief for several years, as a long series of biographies, essays, sermons, poems, and musical scores in her honor shows. Indeed, the suddenness of Gwendoline’s death triggered widespread suspicions that she had been poisoned, specifically by her Borghese mother-in-law, Adele de la Rouchefoucald (1793-1877).

Portrait of Gwendoline Talbot, Princess Borghese by Collati, a Roman artist (1838). Credit: Marc-Arthur Kohn (2012 auction)

Portrait of Gwendoline Talbot, Princess Borghese by Collati, a Roman artist (1838). Credit: Marc-Arthur Kohn (2012 auction)

Happily, Gwendoline’s daughter Agnese survived and thrived. In 1854 she married Prince Rodolfo Boncompagni Ludovisi (1834-1911), became Princess of Piombino in 1883, and indeed lived until 1920. Throughout her life, as ADBL assistant director Carol Cofone has shown (and will continue to show in a book to be published by Rutgers University Press), Agnese sought to emulate her mother’s principles if not actual actions, and also promoted her memory—to the point of working for her canonization as a saint in the Roman Catholic church.

And the Princess Doria? Like her sister, Mary Alethea Beatrix Talbot won wide praise in Rome for her intelligence, cultural attainments, affability, piety, and philanthropy. By the mid-1840s, she and her husband also had a reputation for hosting the most lavish receptions in Rome, after those of the Torlonia. But she too met a premature death, in 1858, following an illness of two years. Mary was aged 43, and left five children, three daughters and two sons. (Two other children had died in infancy.)

The Princess Doria was buried in a chapel behind the high altar of S Agnese in Rome’s Piazza Navona. There Pietro Tenerani planned to create a lavish funerary monument with pseudo-medieval elements, but never fully executed his design. His chief biographer Oreste Raggi says the memorial was of a type to “inspire a sense of deep veneration and almost I would say of terror”.

Detail of portrait in marble by Pietro Tenerani in the Casino dell’Aurora. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome. Photo: TC Brennan

Detail of portrait in marble by Pietro Tenerani in the Casino dell’Aurora. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome. Photo: TC Brennan

For years, among other signal demonstrations of grief, Prince Filippo Andrea V Doria Pamphilj Landi attended a daily 10am mass at S Agnese in his wife’s memory. He closed his many properties to almost all social functions for a full decade. He also had box hedges clipped at the entrance to his Villa Doria Pamphilj on the Gianicolo to spell out MARY in giant letters. Yet the final unification of Italy pulled the prince back into public life. Starting from December 1870, he served as acting mayor of Rome for about four months, and as Senator of the new Kingdom until his death in March 1876, aged 62.

It comes as little surprise that the prolific Pietro Tenerani sculpted portraits of both Mary and Guendalina Talbot, the two most charismatic and beloved Roman noblewomen of his time. Oreste Raggi in his 1880 biography and catalogue raisonné of Tenerani notes that the bust of Gwendoline was posthumous, rendered from a sketch. As for Mary, Raggi explains that the sculptor portrayed her twice, once in life and again (in 1859) after her death.

So where are those portraits? Well, the Galleria Doria Pamphilj has in its “Tenerani Cabinet” busts by the artist in marble of the two sisters, and also one of Prince Filippo Andrea V. The Gallery’s website explains that the Prince commissioned the pieces in 1850. In all three, Tenerani’s style, as Anthony Majanlahti pointed out in his 2006 The Families Who Made Rome, is “icily classicising”. Mary wears classical drapery, though the hairstyle—parted in the center with two long and improbably intricate braids gathered at the top of her head—is contemporary. Meanwhile, Gwendoline’s hairstyle seems an uncanny harbinger to that of Princess Leia in the original Star Wars film trilogy.

From left, in the Galleria Doria Pamphilj, portraits in marble by Pietro Tenerani (ca. 1850) of Lady Gwendoline Talbot, Princess Borghese; Prince Filippo Andrea V Doria Pamphilj Landi; and his wife Lady Mary Talbot, Princess Doria Pamphilj. Credit: Giovanni Rivetti

From left, in the Galleria Doria Pamphilj, portraits in marble by Pietro Tenerani (ca. 1850) of Lady Gwendoline Talbot, Princess Borghese; Prince Filippo Andrea V Doria Pamphilj Landi; and his wife Lady Mary Talbot, Princess Doria Pamphilj. Credit: Giovanni Rivetti

When Nathaniel and Sophia Peabody Hawthorne visited the Galleria Doria Pamphilj in February 1858, this bust of Princess Doria was already in place. Sophia Hawthorne remarked on the marble portraits “of the Princess Mary Talbot Doria (the English lady), by Tenerani, which is very beautiful”, and of her husband, whom she guessed from the work must be “handsome”.

And here’s the important bit. The bust of Mary Talbot in the Galleria Doria Pamphilj is essentially identical with the Tenerani portrait in the Casino dell’Aurora. The (faint) signature P. TENERANI carved on the back of the latter bust completes the identification of artist and subject. So there are two copies of this same work. The main difference is that the Casino dell’Aurora version lacks a pedestal base.

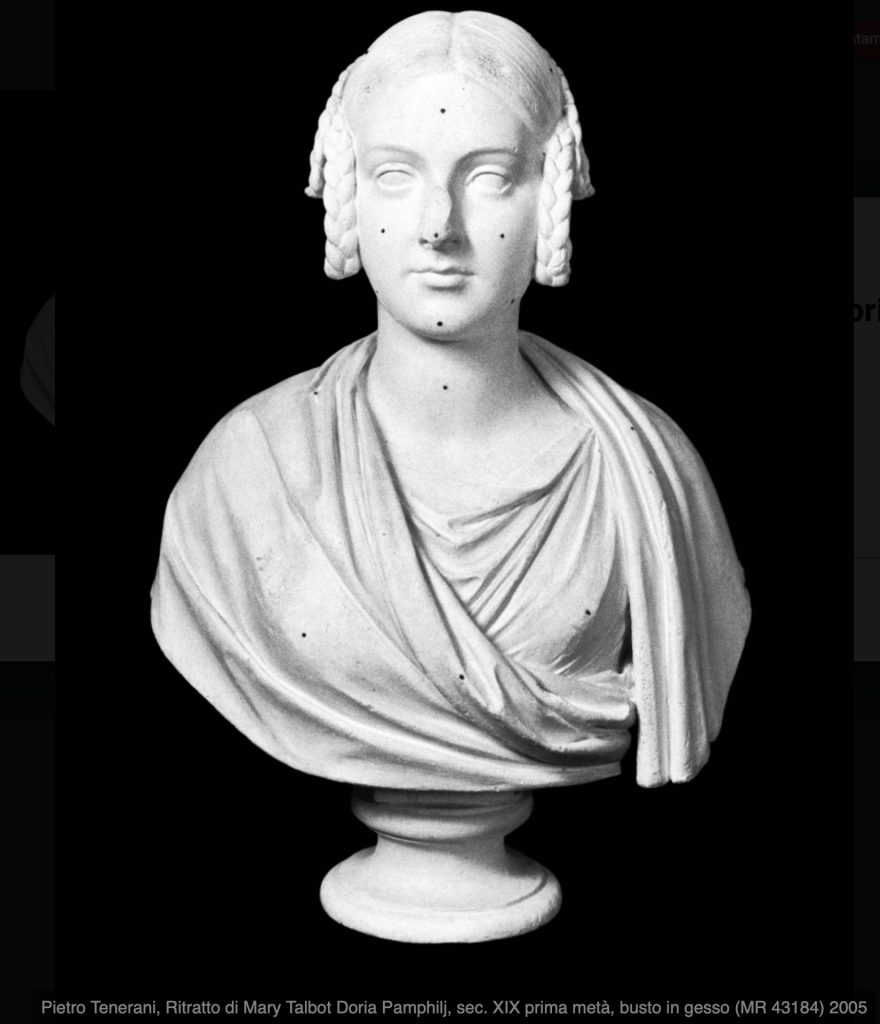

In the Museo di Roma—Palazzo Braschi, portrait in painted plaster by Pietro Tenerani (ca. 1850) of Lady Mary Talbot, Princess Doria Pamphilj. Credit: Museo di Roma.

In the Museo di Roma—Palazzo Braschi, portrait in painted plaster by Pietro Tenerani (ca. 1850) of Lady Mary Talbot, Princess Doria Pamphilj. Credit: Museo di Roma.

There is much more to be said about the sculptor Pietro Tenerani and his portraits of the Talbot sisters. For a start, the Museo di Roma in Palazzo Braschi has a plaster version of the Doria Pamphilj / Casino dell’Aurora portrait of Mary Talbot (marked with reference points), as well as of the Gwendoline Talbot bust. It also has a plaster version of Tenerani’s second attempt at Princess Doria’s portrait, which his biographer dates to 1859; the final work is presumed lost. All these plaster models came to the Museo di Roma from Tenerani’s atelier on the Via Nazionale in Rome, sometime before 1941. In other words, there is enough material to allow an in-depth discussion of Tenerani’s portrayal of the Talbots and its development.

Then there is the question of provenance for our piece, and its display history. One assumes that it was Mary Talbot’s niece, Agnese Borghese, who after her 1854 marriage to Rodolfo Boncompagni Ludovisi brought the marble to the Villa Ludovisi, if not specifically the Casino dell’Aurora within the Villa. But before we attempt to answer these and other questions, it will be necessary to dig a bit more in the Boncompagni Ludovisi archives! Portrait in marble by Pietro Tenerani (by ca. 1850) of Lady Mary Talbot, Princess Doria Pamphilj, in the Casino dell’Aurora. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome. Photo: TC Brennan

Portrait in marble by Pietro Tenerani (by ca. 1850) of Lady Mary Talbot, Princess Doria Pamphilj, in the Casino dell’Aurora. Collection of †HSH Prince Nicolò and Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome. Photo: TC Brennan

Wonderful and charitab

A wonderful and illuminating study of classical portrait style in 19th century Roman Society portraiture.

Thank you for a fascinating insight!