Jun 30, 2020

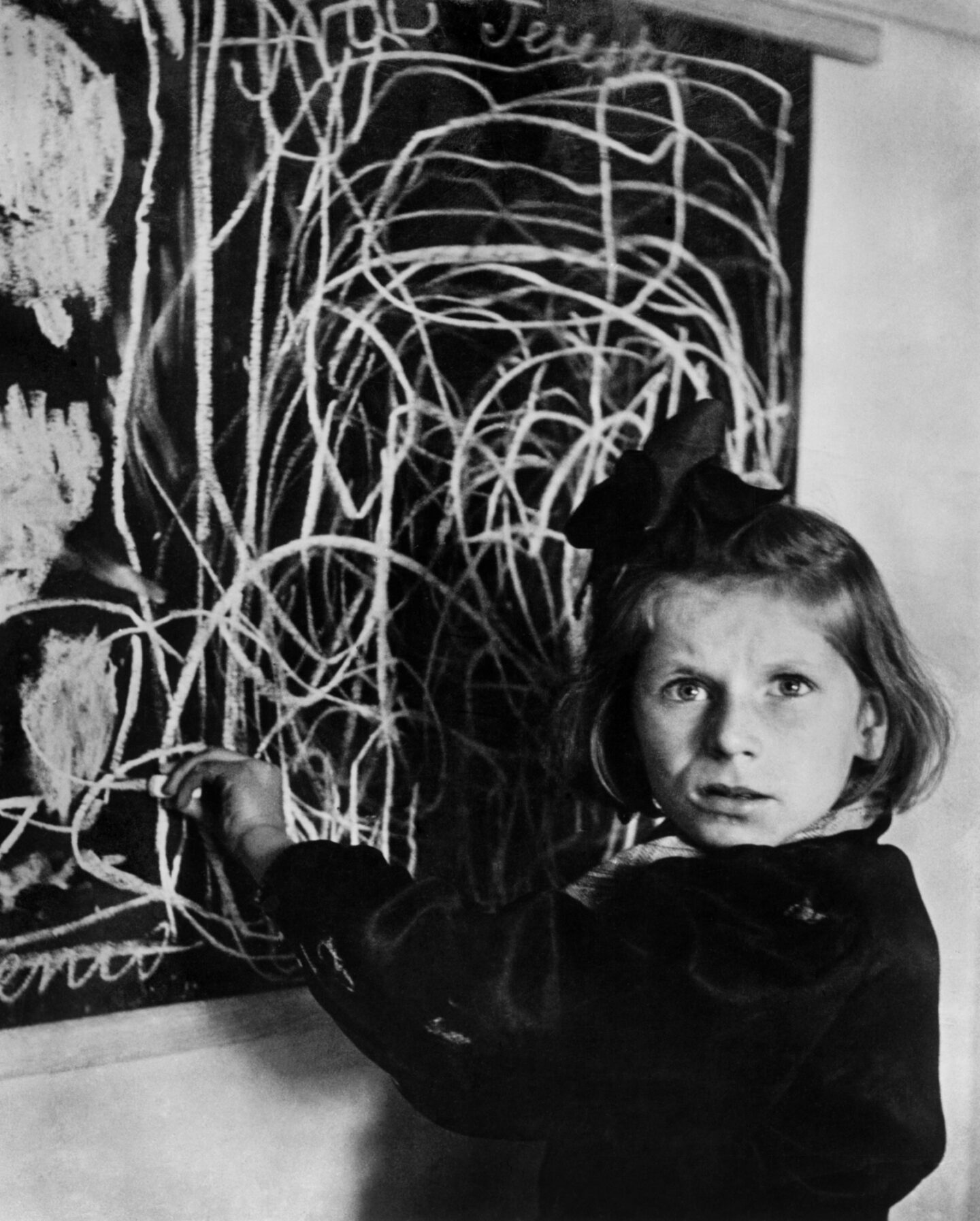

“Tereska” Photograph by David Seymour-Chim. Photograph courtesy of David Seymour-Chim/Magnum, For more information: www.davidseymour.com

ABSTRACT

Is there a Jewish way of not saying things? The years following the Holocaust were a time when many artists, psychoanalysts, and global leaders were focused on two overlapping crises: that of the refugee, children especially, and that of language, as many sensed that human communication had undergone a seismic shift during the war. Drawing from these intellectual and artistic currents were two feature films shot in Europe between 1947 and 1949: Fred Zinnemann’s Hollywood production The Search, and the Yiddish film Undzere Kinder (Our Children), directed by Natan Gross and starring the renowned comic duo of Shimen Dzigan and Yisroel Shumacher. Employing similar cinematic tools, these films nonetheless make very different propositions about the relationships between pain and speech. To understand these differences, I press upon the idea of language communities: Yiddish and Anglo-American cultures, I argue, guide people to different perceptions of the psyche, of love, and of power.

To view a PDF of this article click here.

On December 27, 1948, LIFE magazine featured an image of a young orphan named Terezka, with hair unkempt and wild eyes glaring at the camera. She served as an example of how “Children’s wounds are not all outward.”

1

1

“Children of Europe,” LIFE, December 27, 1948, 17.

The prominence of images like this one in the immediate postwar years recalls David Roskies’s assertion that children and especially “the parent-child relationship became a universal trope” of early post-Holocaust commentary, a topic around which writers could explore their notions of vulnerability, victimhood, and the potential for future recovery.

2

2

David G. Roskies and Naomi Diamant, Holocaust Literature: A History and a Guide (Waltham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2012), 48.

Historians of psychoanalysis have similarly remarked how, at this time, the psychic protection of children became a focal point of public policy as well as scholarly inquiry.

3

3

Michal Shapira, The War Inside (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), esp. 198-238.

In the same moment, film figured prominently in postwar explorations of psychic damage, both in popular media as well as in professional research.

4

4

Alison Winter, “Film and the Construction of Memory in Psychoanalysis, 1940–1960,” Science in context 19, no. 01 (2006): 111-136.

Drawing from these intellectual and artistic currents were two feature films shot in Europe between 1947 and 1949: Fred Zinnemann’s Hollywood production The Search, and the Yiddish film Undzere Kinder (Our Children), directed by Natan Gross and starring the renowned comic duo of Shimen Dzigan and Yisroel Shumacher. 5 5The Search, Directed by Fred Zinnemann (Los Angeles: Warner Brothers, 1948). Undzere Kinder, Directed by Natan Gross (Poland: Kinor, 1949). The similarities between these two films are striking: both were shot ‘on location’ in war-torn Europe and entrusted real-life DP children to play themselves on screen. Moreover, both films foreground problems of speech and memory among the DPs. Both films also stage scenes in which ‘non-survivor’ adults have trouble communicating with these young survivors, because ‘language as usual’ fails them. And, finally, in both films, finding the right words is somehow crucial to recovery—for the child and for the society around them. Yet, each of these two films construes the problem of language, and its relationship to the postwar child, differently. This essay asks how these differences relate to audience—the American movie-house (The Search) versus internal DP venues (Undzere Kinder) — as well as the filmmakers’ respective positions toward Jewish particularity. As these two films dramatize, Yiddish and English may each produce distinct kinds of traumatic silences.

Making The Search

In April 1948, New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther hailed The Search as one of the best pictures of the year: “Frankly, this writer can remember few pictures within our span that have packed such affecting human drama with such important enlightenment, that have been so emotionally stirring and so urgently topical at the same time.” 6 6 Bosley Crowther, “Straight to the Heart,” New York Times, April 4, 1948, X1. Challenging in subject matter, the film nonetheless “balms the pain of a general demonstration with a triumph of individual love.” For this reason, Crowther recommended The Search even to viewers who were “cautious about exposing their sensibilities to distress in the theatre.” Crowther was not alone in praising the film, which was nominated for an Academy Award in directing that year.

That the film, shot in Europe with a cast of mostly unknown actors and non-actors, should be so well received in American movie houses was in no way predictable. In fact, Zinnemann remembers the project as a risky act of defiance, made at a vulnerable moment in his career. Zinnemann, who came from a Viennese Jewish family, moved to Hollywood in 1929 to join the American film industry. He eventually earned a directing contract with Metro Goldwyn Meyer. However, the studio had temporarily suspended Zinnemann’s contract during the war when he refused to make films he considered mindless.

In mid-1946, the Swiss producer Lazar Wechsler invited Zinnemann to make a film with him about children who had been displaced and orphaned as a result of the war. Granted permission from MGM, Zinnemann travelled to the DP camps of Europe, where he researched the film for over a year. Interviewing children personally, Zinnemann also read case histories opened up to him by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). Zinnemann’s dedication to the project was “intensely personal”: despite Zinnemann’s efforts to bring his parents to the U.S. before the war, his father had been imprisoned and killed in Belzec, his mother in Auschwitz. 7 7 J. E. Smyth, “Fred Zinnemann’s Search (1945-48): Reconstructing the Voices of Europe’s Children,” Film History: an International Journal 23, no. 1 (2011): 75-92, here 75.

Zinnemann struggled to turn the children’s stories that he had heard—and which paralleled his own—into a film that would meet his standards of authenticity. After rejecting multiple scripts, in 1947 Zinnemann settled on the story of a single DP boy who was befriended by a plucky yet naïve American soldier. The lead roles were played by actors, two Americans and two Europeans, but set against the performances of non-actor European children, some of them orphans receiving help from DP camps at the time. Regarding his method for directing ‘real people,’ Zinnemann reflected in 1950, “They must be allowed to relive a situation and behave rather than act” 8 8 Fred Zinnemann, “On Using Non-Actors in Pictures,” New York Times, January 8, 1950, X7. —an approach influenced by Italian neo-realism at the time.

Making “Undzere Kinder”

In the winter of 1948, the Polish Yiddish newspaper Yidishe bilder ran a story about the postwar popularity of Dzigan and Shumacher: “Dzigan and Shumacher are overwhelmed with invitations to perform all over the world. They are wanted in Paris, in London (already for the second time), in America, in Eretz Yisrael, in Lithuania and in Latvia.” 9 9 I.S. Goldshteyn, “Zey lakhn oys di idishe tsores,” Yidishe bilder, January 5, 1948, 20-21. The comedy duo’s relationship toward Holocaust survivors was very different than Zinnemann’s. While the two actors from Lodz had been spared the horrors of German occupation, Dzigan and Shumacher had survived the war years in Soviet labor camps in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, and had returned to Lodz, also very much displaced, in 1947. 10 10 John Efron, “From Łódź to Tel Aviv: The Yiddish Political Satire of Shimen Dzigan and Yisroel Shumacher,” The Jewish Quarterly Review 102 (1), 2012: 50–79, here 68-69. James Hoberman, Bridge of light: Yiddish Film between Two Worlds. (New York: Schocken Books, 1991), 330-335. The same newspaper article depicts these performers as integral members of the newly assembled Jewish community in Lodz: “Their apartment (they even live together) is a meeting spot for writers and journalists, artists, and Jewish intelligentsia.” 11 11 Goldshteyn, 21.

The arrival of Dzigan and Schumacher onto the Lodz scene caught the attention of the Yiddish film director Natan Gross. His prewar colleague, producer Shaul Goskind, suggested to Gross that they all work together on a project. The prospect both intrigued and frightened Gross: “I, who had survived the Shoah with my own flesh, said you can’t make a comedy. But, not to make a comedy with Dzigan and Shumacher is impossible.” 12 12 Interview with Natan Gross, Research archives of film, Bemidinat Hayehudim, directed by Gavriel Bibliyovits et al. (Tel Aviv: Matar, Plus, 2006). These tensions between different types of Jewish DP experiences, and between postwar cultural rejuvenation and honest wartime accounting, ultimately inspired the plot of the film. The filmmakers employed realist techniques similar to Zinnemann’s, including on-site shooting and non-professional actors. “This was a story taken from life,” as Dzigan put it years later. 13 13 Shimen Dzigan, Der koyekh fun yidishn humor (Tel Aviv, 1974), 289. They had wanted to make an epilogue that depicted the children in Israel , but filming was never never completed. 14 14 Interview with Natan Gross, Bemidinat Hayehudim archives.

The Search for Mother, the Search for Words

The Search points viewers toward a crisis of language from the very start. In its first frames, UNRRA workers pull open a cattle car door to reveal a mass of silent, fearful young faces. A tender female voiceover introduces the children’s predicament: “They move like machines. Not a sound heard from them.” The children suffer from a problem of communication that demands more than physical care. Even after they have been cleaned and fed, there is “Still not a sound of children’s voices and children’s laughter.”

The only effective way to solve this speech crisis, as presented in the film, is to work through one child’s voice at a time. This process is dramatized in the UNRRA registration room, where ragged refugee children are called up individually to share their stories with the director, Mrs. Murray, who receives help from a multilingual translator. Facing challenges, Mrs. Murray nonetheless makes progress with all but one slight, blonde child who has a number tattooed on his arm. Remembering nothing of his prewar or wartime experiences, he responds to every question either with a blank stare or the non-words: “Ich weiß nicht (I don’t know).” The boy’s inability to speak is inextricably linked with his inability to remember his parents. That is, the film points to a primary memory of maternal care as key to a functioning linguistic faculty. Conversely, the boy’s incapacity to speak also prevents him from receiving the nurturing he needs. The boy mistrusts adults, their words, their houses, and their plans to heal him. While travelling on a transport van to a special camp for orphans, the boy runs off along with other children. But unlike the others, this speechless boy does not return, instead opting to roam alone amid the ruins.

Perhaps in order to avoid causing too much “distress in the theatre,” the film hastens to imply that a solution will be found: a voiceover with flashback scenes reveals that the boy is Karel Malik, who hails from a loving intellectual family in Prague. Soon thereafter, we see postwar images of his beautiful mother, trekking between DP camps in search of her son. Frustratingly, Karel’s silence prevents their reunion; since the boy cannot speak, he has left no documented trace of his whereabouts within the DP camp system and his mother cannot find him.

In keeping with Zinnemann’s preference for individual acts of conscience over institutional efforts, it is a single “decent man” who sets Karel back on the track towards language, and ultimately towards maternal shelter. A good-humoured, young GI, Steve, discovers the boy amid the ruins and draws him into his care by offering bits of food—as one might do with an animal. Clumsy though his methods might be, Steve’s good will and patience pay off. The boy learns to trust the soldier, moves into his quarters, and accepts his offers of food and clothing.

Still, Karel (who does not yet remember his own name) remains silent. “Don’t you speak anything!!?” Steve shouts in frustration. Steve finally makes a breakthrough when he, jokingly, places a shot of whisky under the boy’s nose and says, “Here, have a drink.” Finally, the youngster speaks: “No.” It is this single, restored sensory-verbal connection, stumbled upon by chance, that enables his speech to return. After “no” comes “yes”—which the boy utters when offered chocolate. Bitter and sweet tastes, clear, transcultural signifiers drawn from the world of childhood innocence, are what restore his capacity to communicate. Then, facing a fresh symbolic slate, not unlike Adam and Eve, the boy appropriately receives a name in this same moment. “Jim, I’ll call you Jim,” Steve announces.

The plot cleanly demarcates the difference between a traumatized, silent child and a healthy, speaking one. As soon as “Jim” can talk, he can also smile, socialize and—eventually—remember. Yet the process does not unfold smoothly and Zinnemann still does not shy away from self-critique. The film reveals Steve’s Americano-centrism, teaching the boy words like “New York” and “Abraham Lincoln” as if they were as basic as “book” and “table.” It also underscores how American bureaucracy, even if well-meaning, remained out of step with real human needs: Steve’s requests to bring Jim back to America under his charge are repeatedly denied.

Still, the force of the boy’s restored sense-word connection overpowers these cultural biases and shortcomings. He connects an image of motherhood, stirred by his encounter with another American military family, to a picture of a fence, which appeared in a magazine. The two images allow Jim to reconstruct the most important element of his story: he had a mother, who was violently taken away from him in a concentration camp. Once Jim remembers her existence, he can then know what and whom to search for. Surely part of the “balm” to which the 1948 reviewer referred, the film then provides a happy ending. Through a series of fast-paced chance occurrences, the two reunite.

Their reunion scene once again shows vision and sensory perception as crucial to healing speech. Mother and child are allowed to discover each other first with their own eyes, and only then in their own tongue. “Karele!” she shouts, using his original Czech name and “Maminke!” the Czech diminutive, is his response. Here it is confirmed that the boy has regained universal skills of communication and that American English was merely an incidental entry point. The same psychic-cognitive faculties that Steve helped him recover apply just as well to his native Czech.

Having traced the plot of the film with speech as protagonist, the title The Search appears appropriate indeed. There is a search for the voice that has gone missing. It is found. This happens through the carefully focused story of an individual, with a well-defined problem and a well-defined solution. According to the film, the Holocaust did violence to language by shutting down individual human instincts. In response, the capacity to communicate reemerges thanks to person-to-person care, which restores emotional security, civilized behavior, and the cognitive processing of the senses.

Beyond its timely plot, the positive response from American viewers to The Search seems related to the film’s “figural plasticity.” 15 15 Michael Bernstein, “Homage to the Extreme: the Shoah and the Rhetoric of The focus on individual emotions and decisions, “the triumph of love” over political or national concerns, enabled the story to travel across cultural space. Did the film also succeed, perhaps, because it was not overtly Jewish? Atina Grossman critically groups the film among other postwar works that de-Judaicized the Holocaust. 16 16 Atina Grossmann, Jews, Germans, and Allies: Close Encounters in Occupied Germany (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 331–332 and 183–184. J.E. Smyth convincingly counters that there were subtle signs of Jewishness woven into the film, which would have caught the attention of those interested, like a supersonic dog-whistle: the boy comes from an intellectual Prague family and is initially seen wearing a yarmulke-like black cap. 17 17 Smyth, 85. Moreover, a journalist of the day reported that Zinnemann considered making a sequel to the film about the arrival of Jewish orphans in Palestine (yet another surprising point of parallel with Undzere Kinder). 18 18 A. H. Weiler, “By Way of Report,” New York Times, May 9, 1948, X5; A. H. Weiler, “Promissory Notes,” New York Times, December 26, 1948, X5. As it is, the film leaves room for one to recognize a Jewish story, but does not commit to it; in fact, the film does not commit to any national or cultural framework as the proper lens of interpretation. Even the American perspective is decentered by making the young protagonist and his mother return to their Czech identities at the film’s close.

The Importance of (Not Always) Being Earnest in “Undzere Kinder”

This film also opens with a voiceover. Incorporating documentary footage, the monologue contextualizes the drama as taking place on the heels of Holocaust horrors and, as in The Search, announces the theme of language: “Undzere kinder (our children)—how much meaning lies in these two simple words.” Rather than silent voices, here there is a different kind of communication problem: too much meaning, too many different possibilities have been mapped onto the same two Yiddish words to be able to speak them complacently. The quickly flashing sounds and images in the background dramatize this semantic multiplicity: we hear a triumphant march sung by a children’s choir, but then quickly jump to pictures of empty shoes and abandoned dolls. The contradictions extend beyond simultaneous projections of life against death. The opening segment also bounces between startling expressions of sensitivity and pat political propaganda, especially as it ends, naming the child survivors “the new youth of liberated Poland.”

In contrast to the process of search, discovery, and healing that characterizes Zinnemann’s film, perhaps we could call the way that Undzere Kinder frames the same problem “shatnez trauma 19 19 This phrase was inspired by the comments offered by the writer and literary scholar Adi Sorek, when she introduced the film at a Yiddish Tsimer screening for the Department of Hebrew Literature at the University of Ben Gurion in the Negev, March 15, 2011. ”—a taboo mixing of elements that should normally be kept apart. This blending appears taboo and unexpected, both within the world of the film and according to the rules of our current (early twenty-first century) Holocaust discourse.

While The Search uses its first scenes to dramatize the problem that must be solved, displaying ragged children in need of help, Undzere Kinder does not readily define such a problem on screen. The first scene shows a group of clean-cut youngsters on an outdoor stroll, accompanied by a dependable caretaker. They notice a sign for a matinee performance by Dzigan and Shumacher. Upon the children’s pleading, the woman agrees to take them. The caretaker and orphans are able to communicate with one another not only verbally, via the Yiddish language, but also socially, negotiating norms of behavior, appropriate rewards, and pleasurable pastimes.

What takes place at the comedy show punctures this message about the continuing functionality of language. After panned shots of a large, enthusiastic audience, the actors appear on stage. “A yid bin ikh gevezn un a yid vel ikh zayn/ mirtseshem veln mir nokh trinken vayn! (I was a Jew and I’ll remain a Jew/ God willing, we’ll all drink wine!)” recites Dzigan. This inflated verbal declaration of Jewish continuity is matched by an overconfident performance. The comedians depict life in the ghetto with song, dance, rhyme, and light-hearted costumes that could have been worn in an interwar production. Suddenly, in response to the show, one orphan from the group lets out a loud whistle. The crowd turns around in shock and the demonstration of cultural confidence on stage is cut short.

Here, the child survivor does not oppose complacent, functioning language with silence, as does Zinnemann’s Karel Malik, but with a loud interruption. The child does not await an opportunity to reconnect sensation with words, but rather acts to dislodge the quickly resurrected symbolic conventions he sees. The message within this fictional scene—that it is too early to fall back on the familiar language we once knew—was also enacted in reality, during the film’s shooting. Director Natan Gross recalls how, for background footage, they filmed a large audience gathered to dedicate a new theatre: “The respectable crowd arrived to hear the celebratory speeches of the commissars.…Dzigan went up to a balcony and started shouting, ‘Ooh! Ah!’ and interrupted the speeches. The whole audience turned around and I filmed it.” 20 20 Gross Interview, as above. With their bold ruse, the filmmakers interrupted the trouble-free public speech of postwar Polish politicians, just as the boy interrupted the comedians’ comfortable humor.

In response to this breach, the comedians and the children have an exchange. Taken backstage by their caretaker, the children apologize but also justify their complaint: “A poor man didn’t have the strength to dance the Kozak in the ghetto.” They explain to the actors that in order to “play the ghetto,” they would not simply have to depict conditions as having been worse, but to employ a strain of Yiddish speech that is different than the one they know. Explaining their real methods of survival becomes a vocabulary lesson:

Boy: He was a khaper is what he was!

Dzigan: A what?

All children: A khaper!”

One boy steps forward to explicate what being a khaper (pickpocket) entailed. Almost every third word is some idiom of ghetto slang. Dzigan and Shumacher glance at each other in amazement, as both the content and the language required to define khaper sound so new. “We need to learn from these kids,” Shumacher concludes.

The film seems to have cleared the way for a problem-process-solution plotline to emerge: the child survivors know a secret language of suffering and the adult non-survivors have to document it and learn it. But, in the spirit of shatnez, that is also not what happens. In this same scene, another boy emerges from behind a curtain dressed as an SS man, with his hand raised in a ‘Heil Hitler!’ salute. If earlier the children objected to artifice, Holocaust humor specifically, now they enjoy it. All gather around the farcical SS man in joyous laughter.

This dynamic of taboo blending continues, with the flips between horror and humor, verisimilitude and artifice only becoming more extreme. Dzigan and Shumacher are invited to visit the children at their home, the Helenowek Colony outside of Lodz. Their journey to the home is pastoral and optimistic. The two comedians perform a Goldfaden song in the sun as a Jewish farmer gives them a ride on his horse-drawn wagon. Upon arrival, Dzigan and Shumacher join the children for a celebratory meal, during which both young and old take turns performing. Now, artifice is welcome on both sides. The children’s dance looks much like the “Kozak” to which they objected in the Lodz performance. For their part, Dzigan and Shumacher put on a show that is arguably more artificial and lighthearted than their earlier number that caused such offense. The film thus affords Jewish survivors permission to change their tack, to intermittently act happy, if you will.

This evening performance scene also includes a key visual image: all members of the plot—children, caretakers, and guests alike—sit around a table together, under one roof. They are required to view whatever comes on stage together. The pleasure, problems, and lacunae of their presentations must all be faced through this communal framework. How different a forum of collective healing this appears to be than the tableus of intimate connection between Karel and Steve, the boy’s single, most trusted companion.

This long segment of playful theatrics and humor, stretching from the outdoor musical interlude to the indoor performative exchange, comes to an abrupt end when the children and staff retire to their bedrooms for the night. Sitting up on bunk beds in their crowded sleeping quarters, the children take turns remembering. Rather than a single narrative of separation and reunion, here the children present multiple stories of unredeemed pain, telling how each child survived, though his or her mother did not. The stories are reenacted with flashbacks that pull no punches in terms of acting style, gesture, and visual imagery. They are striking—perhaps even melodramatic—in their attempts to show and tell as much as possible.

Even Dzigan and Shumacher find that these rapid-fire testimonials are too much for them, as they eavesdrop in the hallway. Dzigan implores his partner to leave the Helenowek camp with him right then and there. Shumacher persuades him that they must remain residents of the “nightmare house,” at least through the night. Here too, the actors’ commitment to dwelling within a shared communal physical structure, even when they would prefer to do otherwise, points towards a parallel commitment to confronting Holocaust wounds under the shared roof of the Yiddish language, within the bounds of East European Jewish cultural heritage, whatever that might now mean. Indeed, within the cinematic world of shatnez, attempts at memory that go over the top and strains of speech that are overly direct must also be heard and tolerated.

The morning presents the most dramatic reversal thus far. Dzigan and Shumacher open their windows to find the children playing joyfully in the sun. Film critic Ira Konigsberg sees this scene as proof that the children’s testimonial act of the night before “has been a kind of purgation, has, indeed, helped the children to move from their nightmares and into the sunny morning.” 21 21 Ira Konigsberg, “Our Children and the Limits of Cinema: Early Jewish Responses to the Holocaust.” Film Quarterly 52, no. 1 (1998): 7-19, here 14. Yet, the film does not seem to fully support such a linear assessment of therapeutic resolution. The camera makes no connection between the night’s confrontation with memory and the morning’s cheer. The switch is simply asserted. Moreover, the slow, painstaking therapeutic progress that Zinnemann traces in Karel Malek should serve as a counterpoint to this rapid mood leap. Likewise, the film makes no guarantees that horrific memories will not possess the children once again the following night. The switch appears not only unearned, but also temporary.

The characters accept the unresolved contradiction between night and day. These children “can expect a brighter tomorrow!” Dzigan declares. This hyperbolic optimism appears as part of the shatnez mix. It is another way to speak about this postwar moment that is allowed to collide with the admissions of pain and vulnerability, as well as the critiques against hasty complacency that the film has also voiced.

The reaction of the film’s first audience speaks to both its lack of resolution as well as the boldness of its internal contradictions. The Communist Polish government, which had originally approved the production, blocked its distribution. Shaul Goskind, the only member of the creative team left in Poland after its completion, managed to save two copies of the film. He sent one to Israel, where it was screened in 1951 in both Tel Aviv and Haifa. These audiences, likely including many non-survivors still learning about the Jewish catastrophe, reacted with shock to the children’s stories. 22 22 Konigsberg, 12. Likewise, a critic from the time disapproved of the sharp transitions between humor and horror. 23 23 David Zakai, “Sratim,” Davar, July 27, 1951, 9. On the other hand, as Gross recalls, a copy of the film was passed around eagerly amid the Israeli transit camps (ma’abarot), where newcomer survivors were temporarily housed. 24 24 Natan Gross Interview, as above. Perhaps for the same reasons that the Tel Aviv and Haifa audiences found the film distasteful, it gave rise to some sense of recognition among the survivors living in such a state of flux.

Jewish Ways of (not) Saying Things

Learning from these films, it appears that there is more than one ‘Jewish way of (not) saying things.’ Both films were inspired by Jewish experiences and reached different Jewish audiences. The difference between The Search and Undzere Kinder cannot be reduced to a measure of Jewishness. Importantly, though, the two films propose different solutions to the crises of Jewish speech and wellbeing after the war. The Search commits to ethnic transcendence for the sake of healing: Zinnemann’s search for language hinges upon the child’s capacity to reconnect bodily sensation with words. For this process to succeed, all those involved must leave ethnic and national distinctions aside. By contrast, Gross and his creative team made a movie about restoring postwar communication within the Yiddish speech community specifically. This attempt to remain together around the same table, under the same roof of a prewar communal language, requires a tolerance for mixing and blending. As a result, the film forgoes both the promises of immediate therapeutic progress as well cultural transcendence—creating a cinematic message that resonated with a limited audience at the time. In return, Undzere Kinder is able to render East European Jewish victims, children in particular, as more than the recipients of linguistic repair. They become agents of linguistic critique.